Autumnal colours along the Trent and Mersey Canal near Hopwas, November 2020 © Steven Cheshire, Transforming the Trent Valley 2020

Staffordshire in Autumn

The annual rut

Autumn marks the year's main event for our largest land mammal, the red deer; it's mating season. Having spent the rest of the year in single sex herds, the annual rut sees the dominant male rounding up his harem of females. Younger males, and indeed many of the females, have other ideas, and the result is one of the most dramatic events in the wildlife calendar. Stags roaring, heads tossing, and antlers clashing, battle ensues.

Stags let out great roars as the dominant male does his best to defend his hinds (mature female red deer) from young pretenders, strutting back and forth, tossing his antlers in the act of showmanship. The battle ensues with those not intimidated by his bellowing and bravado. Stags clash, linking antlers and shoving each other. It may look dramatic, but this is a ritualised fight, aiming to settle the dispute and sort out who's boss, rather than inflicting damage.

Early morning is a great time to try to see males performing, as the low, golden light and cold, dewy air create the perfect autumnal atmosphere, particularly for photographers.

Fallow deer also rut during autumn and are often easier to see in our county's forests. If you do encounter deer, always keep your distance (ideally over 100 metres away), never approach them or feed them and always keep dogs on a lead where deer are known to roam.

Wonderous wetlands

Our wetlands become a hive of activity as our migrant birds visit to rest and feed. One of the first waders to return to the UK is the green sandpiper, sometimes as early as June! During summer they breed in Russia and Scandinavia, though occasionally a pair or two nests in Scotland. Most summer and autumn visitors just stop off on their way to southern Europe or northern Africa, but some stay in the UK for the winter.

Green sandpipers have a very dark, blackish-brown back, speckled with faint, fine white spots. The head and breast are a slightly paler, streakier brown. The belly is very white, with a sharp distinction between it and the streaky brown breast. The long legs and fairly long bill are greyish green. In flight it shows a white rump and a white tail with thick black bars, as well as very dark underwings.

They’re often found on inland waterbodies, picking their way around the muddy margins. They can turn up on surprisingly small, muddy puddles. They’re usually on their own, rather than in flocks. Like other sandpipers, they bob their body up and down as they walk.

Green sandpiper - Pete Richman

Puffballs and earthballs

Common puffballs appear in woodlands, grasslands and raodsides between July and November; their pear shaped body is 3 to 6cm tall. Its body is covered in pearl like attachments, called pyramidal warts. As the fungi mature, these fall off leaving the fruiting body covered in scars and creamy in colour. As the fungi gets older it will develop a dark area at its apex, this is where its spore hole develops, this hole when fully formed will shoot out thousands of spores at a time when knocked by passing animals or when hit by raindrops. One thing that distinguishes this from the common earthball is its visible stem which looks a little bit like an inverted cone.

Common earthballs are often found on animals paths in woodlands and heathland as they prefer the compact soil and acidity that this habitat provides. They are round in shape, can be up to 4-12cm large, unlike puffballs they are dirty-yellow to ochre-brown and covered in coarse warty scales in irregular shapes. Common earthball may not be deadly, but it is poisonous and is responsible for lots of mushroom poisonings in the UK each year. It might be because they can be confused with common puffballs, which are edible. In the past, common earthballs were sometimes even passed off as truffles. If in doubt don't touch or eat it!

Nature's finale of colour

Surely one of the most loved aspects of autumn is the spectacular show of colour nature provides? But do you know why leaves die and drop?

Leaves are a tree’s way of collecting energy from the sun. They’re green due to the chemical that allows them to use the sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into carbohydrates – the building blocks for growth. All through spring and summer the tree benefits from daylight and warm weather, but as autumn draws on the days get shorter and the weather colder and windier, so the tree has to get ready for winter.

Leaves are not frost-hardy – if the water inside the cells freezes, the cells rupture, much like a frozen lettuce leaf, leaving the tree covered in useless, unproductive leaves. To avoid such damage and loss, the tree withdraws all the useful stuff from its leaves and then sheds them. Thus it actively protects itself from frost damage and the danger being blown down as winter gales catch the leafy canopy like a ship in full sail, ready for a fresh start with new, undamaged leaves in the spring.

Common beech (Fagus sylvatica) woodland in autumn, Cairngorms National Park, Scotland, UK - Mark Hamblin/2020VISION

A feast for little and large

Brambles (blackberry plants) are a woodland-edge species, which means that hedgerows suit them well. Naturally, they grow towards the light, so long canes sprout out from the shade into the open. Left to their own devices, when these canes touch the ground they develop roots and then send up new vertical shoots.

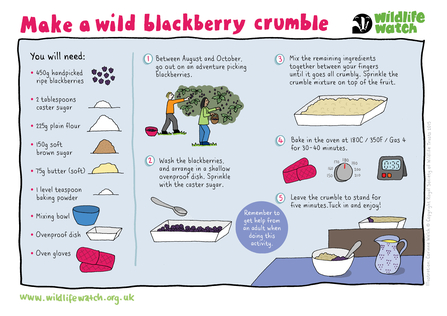

Blackberries are hardy, determined, and can spread rapidly to form an impenetrable thicket – and you can guarantee the best-looking fruit will be right out of reach! August and September are the best months to pick wild blackberries - we've got the perfect crumble recipe for you to follow below!

Wildlife Watch - Make a wild blackberry crumble

Download our wild blackberry crumble recipe

But be sure to leave plenty for wildlife to enjoy. The fruit is enjoyed by a wide range of wildlife, from foxes right through to birds.

As daylight fades the fruiting period finishes. Legend has it that after the end of September, the devil spoils the blackberries, as the story is that that a blackberry bush broke his fall from heaven!